the battle of tannenberg

JULY 15 1410

the battle of tannenberg

JULY 15 1410

(Also called Battle of Grünwald or Zalgiris)

From the book « Samogitia » written by Chas. L.Thourot Pichel

After the Samogitians inflicted heavy losses on the Teutonic Order in their furious and successful insurrection of 1409, some neighboring countries, aware of the details of the battles, assumed that the power structure of the Teutonic knights was broken beyond repair. Motivated by this appraisal, they readily moved in opposition to challenge the Teutonic Order's sphere of influence.

One of such moves was taken by King Jagello of Poland, who placed the princely houses of Pomerania and assumed the new additional title of Prince of Pomerania. This action provoked the Order bitterly and the Knights quickly regrouped their forces and attacked Poland.

Poland at this time had a small standing army because her nobility was more interested in profitable commercial transactions, rather than getting involved in costly and unprofitable military affairs. The Crusaders seized the Polish fortresses of Driesen and Santoch, thereby restricting Poland's maritime trade.

On August 6, 1409, Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen, of the Teutonic Order, declared war on Poland and within 10 days attacked and captured the Polish city of Dobrzyn and the border fortresses on the Neumark frontier in the west.

King Wentzel of Bohemia interceded in the dispute between the Order and Poland, and a truce was signed on October 8,1409, to last until St. John's Day, June 24, 1410.

King Jagello appealed to his cousin, Grand Duke Vytaut of Lithuania, for aid. Vytaut responded with a positive commitment to help him, against what he considered was a vastly weakened Teutonic army.

During the “truce”, both sides engaged in vigorous diplomatic and recruitment campaigns abroad, as well as in military preparations at home. Diplomatic intrigues during this period are without parallel in history. As time elapsed, the situation became so complicated by commitment of both sides that it was questionable whether anyone could rely on any of them.

The Teutonic Order inquired of Grand Duke Vytaut regarding his intentions. Vytaut, with a “kill them with kindness” attitude, informed the Order that King Jagello urged him to take no military action until St. John’s Day, and that he ordered his subjects to observe peace accordingly.

German merchants responded with generous funds for the Teutonic Knights in hopes that the forthcoming war would devastate Cracow, the great Polish commercial city, and thus permit the Germans to control the future trade routes between East and West Europe.

Kings Ruprecht Of Austria, Wentzel of Bohemia, and Sigismund of Hungary indicated their support of the Order, influenced in their decision not only by sympathies for fellows Germans, but by generous subsidies from the Order. King Wentzel was given 60,000 florins by the Order in repayment of costs of friendly mediation. Wentzel confirmed pre-war pacts and frontiers and adjudged Dobrzyn to Poland, and Samogitia to the Order.

Neither side was to assist the pagan Samogitians or “Saracens” as they were called, nor employ the services of the latter. This put King Jagello in an untenable position, because he knew it was impossible for him to deliver Samogitia to the Order. He indicated great dissatisfaction with the decision and had no choice but to turn it down. King Sigismund of Hungary had urged the Order to stand firm in this dispute, and further encouraged them by negotiating an offensive-defensive alliance with them. He was to receive 300,000 ducats and to attack Poland from the south after the expiration of the “truce”. Sigismund's mercenary troops were to be paid by the Order. After a victorious war... the Order was to have Samogitia, Lithuania, Dobrzyn and Kujawia; while Sigismund was to get the bulk of Poland, including Moldavia, Podolia and Halych-Ruthenia. A clause in this pact stipulated that Sigismund would go to war only in the event that the King of Poland would employ the “heathens” in his strife against the Order. By “heathens” they meant Samogitians. In March of 1410, the Order paid Sigismund an additional 40,000 florins.

Jagello and Vytaut also tried to lure King Sigismund to their side, attempting at least to neutralize his position. They were to proceed to Kesmark in Hungary for talks with Sigismund, but for unexplained reasons the nobility of Poland dissuaded Jagello from going. Vytaut went to Hungary alone with an entourage of Lithuanian and Polish advisers. Vytaut sought Sigismund's assurance that he would keep peace, and Sigismund in turn tempted Vytaut with the offer of a royal crown for Lithuania in exchange for an alliance with Hungary against Poland. Vytaut refused the offer, and on departure (in which half the town burned down) he barely escaped being killed by a crowd of Hungarians. He returned to Jagello in May 1410, and related the details of his mission. Then in his return to Lithuania he again barely escaped being killed by Teutonic Knights, who specifically tried to intercept this entourage because there was no “truce” with Lithuania, which would prohibit such an incursion by the Order. These strange happenings certainly had the earmarks of a coordinates plot to dispose of Vytaut.

By the end of May 1410, it became evident that Vytaut of Lithuania was the culprit or central figure opposing the Order. Vytaut issued war orders to all of his governors, and mobilization plans went into effect immediately. Roads and bridges were repaired, meat was cured, and grains were stocked at designated bases, when the Teutonic Order, fearing that Lithuania might complete war preparations before they did, proposed to Vytaut a formal truce until sundown of St. John's Day, he readily agreed, on May 26, 1410.

By a sheer stroke of brilliant diplomacy, Vytaut neutralized the Livonian branch of the Order by coming to an agreement with Landmeister Konrad von Vietinghoff to the effect that either side would forewarn of forthcoming hostilities three months in advance. Vytaut urged the Livonian Order to look over their shoulders into Muscovy, because the Tatars recently had devastated Moscow and could be influenced to march into the Order's territory if it were undefended.

Vytaut became distrustful of the Polish nobility when his spies informed him of Poland's failure to keep up with the timetable, and of the enemy's reaction on her frontiers. He knew that emissaries of the Order met Jagello in secret on several occasions for “peace talks”.

The wealthy nobles of Poland thought King Wentzel of Bohemia rendered a just decision in the dispute with the Order, and they became reluctant to pursue any course that would lead to war. They began to pressure King jagello into changing his mind. They refused to supply Jagello with necessary funds for war preparations, and they continued to delay conscription of troops from their respective districts. It is quite likely that Jagello would have been overthrown at this time if it were not for the influence of future Bishop Zbigniew Olesnicki, who sided with Jagello.

Grand Duke Vytaut by-passed both obstacles set up by the Polish nobility to thwart King Jagello's war efforts. He loaned Jagello large sums of money to hire mercenary troops abroad so that he could pacify his apprehensive nobles, who desired to keep enough of their troops in Poland to defend the homeland against a possible invasion by both the Order and King Sigismund of Hungary.

Vytaut's staff work was done in utmost secrecy. His final move was an appeal to the Samogitians to join his forces without anyone knowing that these “heathens” were to play the main part in his battle plans. To his knowledge, there were no other troops that were capable of maneuvering in combat with the expertise to the Samogitian cavalry. After suffering his great loss in the battle of Vorskla without these cavalry units, he realized that it was imperative to have them in his ranks if he desired an ultimate victory over the Teutonic Knights. He took extraordinary precautions to prevent friend and foe alike from learning of his plans to use the “heathen” Samogitians in battle, because this move would most likely alarm King Jegello, who feared that such a move would precipitate an invasion of Poland by King Sigismund of Hungary, under the terms of his pact with the Teutonic Order.

Vytaut had a most difficult time persuading the Samogitians to fight on his side in the forthcoming battle. The princes and Elders of Samogitia were reluctant to forgive him for his previous actions that were so detrimental to Samogitia's autonomy. Vytaut's methods of this type of diplomacy are exposed in Henrik Sienkiewicz’ book, The Teutonic Knights : “With Vytaut, everything is credible, for he is a man quite different from others, and is assuredly the most cunning of all Christian lords. If he desires to extend his rule towards Ruthenia, then he makes peace with the Germans; but when he has gained what he set before himself, then he is up and at the Germans anew. They cannot deal either with him or with unhappy Samogitia. One day he takes it from them, another day he gives it back... and not only give it back, but himself helps them to crush it. There are some among us, yes, and in Lithuania too, who take it ill of him that he plays thus with the blood of that unhappy people”.

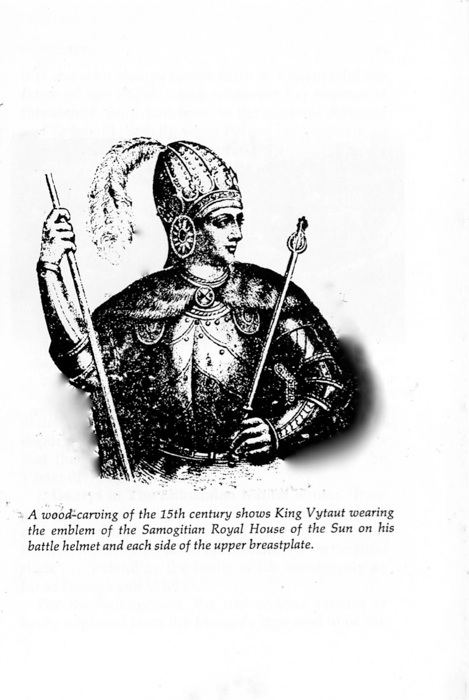

The Samogitian Elders declared to Vytaut that they had no king because their crown prince was only a child, and according to tradition, only their king could lead them in war. Vytaut explained that his mother was a collateral descendant of the Royal House of Samogitia, and therefore he was qualified to act as king for them in this battle and to wear their insignia.

Lithuanian historians sometimes use this incident as a proclamation of Vytaut's becoming king of Samogitia, but this is a completely erroneous assertion. For centuries imaginable, the Samogitians preserved the custom and tradition of the hereditary rights of the youngest male child to succeed his father as king. This most cherished and sacred tradition was never lost because of a play on words, nor the fancies of historians.

The Samogitian princes and Elders, beguiled by Vytaut's persuasiveness, finally yielded to his pleas and mobilized a force of 9,000 cavalrymen, 3,000 infantrymen, and a much smaller group of artillerymen to operate the 10 cannons they possessed. Vytaut very explicitly admonished the Samigitians that neither he nor his cousin Jagello were permitted to use them as any part of their army, lest other countries should become involved against them. In this battle, Vytaut assured them, Samogitia's enemy finally would be disposed of for good.

By the end of the “truce” the Samogitian spies had acquired information on the complete composition of the Teutonic army. This was always their first move in preparing for battle, and based on this information they would make their own plans accordingly. Vytaut, as commander of the allied armies, accepted the Samogitian military proposals, knowing the selected battle site would give the Samogitians complete mastery of the terrain, enabling them to lure the Teutons into a trap wherein they could be annihilated. Vytaut was confident of Samogitian expectations from many previous experiences he had with them in combat. He also remembered that because neither he nor his allies were able to master the Samogitian techniques en 1399, when he attempted to defeat the Tatars of Tamerlane (with an all-Christian army without the pagan Samogitians), he lost the battle of Vorskla.

Because of the secrecy under which the Samogitians were to become involved in the forthcoming battle, Vytaut arrange that they should not be distinguished in inform. They were also to remain in the rear of his army, undetected by his own formal troops until the proper time. The Samogitians were to blend in with the native area, in the manner of poor peasant farmers or woodsmen.

When the “truce” ended June 24, 1410, the armies of both sides promptly moved at various points to cross the borders, employing diversionary tactics as a screen for their objectives. But again an extension of the “truce” to July 4 was arranged, in hopes for peace.

In the next few days of negotiations for peace, Vytaut put on an impressive show of force. He paraded the allied armies, divided into their respective “banners” to impress the guests, but his real motive was to assure the peace negotiators that the “heathen” Samogitians were not a part of his army.

During the peace interval, while negotiations were proceeding, King Sigismund of Hungary acted as mediator. Simultaneously, scouting units of the Samogitians were probing as much as 30 miles behind the Crusader's line, to keep up to date with the enemy situation of that they could evaluate his capabilities at the moment.

The peace talks failed. Apparently, as some authorities believe, both sides used the peace talks to gain time for completion of their war preparations as they jockeyed their respective armies to more favorable positions.

The Poles voiced discontent at the pace of the march from place to place, and grumbled of their “rights” and other things. The Polish nobles threatened to disengage their troops and tried to intimidate King Jagello to their point of view. But Jagello had a Lithuanian regiments, commanded by his nephew, son of the Prince Kaributas, assigned by Vytaut for protection and other precautionary reasons.

At this low point in the morale of the Polish troops, an unexpected incident occurred which changed the course of events.

On their return from a scouting mission behind enemy lines, two Samogitians took a golden chalice from an altar of a Catholic Church in the village of Lautenburg and were apprehended by Vytaut's formal troops. The polish nobles were enraged at this atrocity and were using this incident to divorce themselves from Vytaut's army, but Vytaut acted swiftly ; ( The fact that the Samogitians were captured and failed to complete their mission carried a death penalty. As pagans, they didn't know of the sacrilege committed in the eyes of Catholics.) in summary judgment he condemned the two men to erect a scaffold and to hang themselves in full view of the allied troops. This created a tremendous impression on the Poles, and, according to Polish historian Canon Dlugosz: (Canon John Dlugosz' father had been among the combatants in Tannenberg. Because of this first-hand knowledge, his admirable description of the battle is well respected.) “The grand Duke instilled so much terror in all the knights that they shook like aspen leaves before him”. Polish complaints ceased, and the next day well-disciplined armies marched again to their appointed locations for battle.

The night before the battle, on July 14, the armies under Vytaut made what appeared to be his last move in preparation of the coming battle. The Teutonic forces then made counter moves on both sides before the encounter. But Vytaut made an additional pre-dawn move to his selection for the battle site, which enabled him to rest his troops properly before Teutonic Knights would attack.

Grand Duke Vytaut of Lithuania fighting at Tannenberg-Grünwald-Zalgiris

At dawn of July 15, the epic day of battle, the Teutonic Knights were chagrined to find that the Lithuanians had changed positions, which forced them to do likewise, belatedly. This deception on the part of the Lithuanians forced the Teutons to expend a great deal on energy before the actual battle.

The allied armies of Vytaut consisted (Ghllebert de Lannoy, an ancestor of Franklin D. Roosevelt, wrote that Vytaut had a personal entourage of 10,000 saddled horsemen) of 40,000 Lithuanians, 12,000 Samogitians, 500 Tatars, and 14,000 Poles – half of the latter being mercenary troops, mostly of Czech origin. Most historians fail to take into consideration the fact that many troops of the Polish army remained at home under orders of their nobles to protect their homeland in event of a possible attack by Hungary or Bohemia. The Poles were well aware of the intricate intrigues developed by the Teutonic Knights, and especially of their mutual assistance treaty with Hungary should the heathen Samogitians fight in alliance with Poland or Lithuania. Furthermore, they were chastised by the Grand Master of the Order, who asserted that a Christian knight who fought the Samogitians against the Order ought, in justice, to be put to death.

The Lithuanians had 60 cannons (Grand Duke Vytaut in 1410 A. D. had the largest cannon foundry in Europe, situated in his city of Vilnius), in position for the battle, which included the 10 Samogitian cannons. The Poles had no artillery.

The Teutonic Knights had a force of at least 45,000 troops, and about 5,000 of them were Polish troops from Silesia, Pomerania, and Poland, mostly mercenaries. They had 20 cannons for use in battle. The reason the Crusaders were outnumbered in that they were unable to supplement their forces with recruits from both France and England because these two were at war with each other.

On the clear morning of July 15, 1410 both sides completed their final preparations and awaited attack from each other. In the meantime, the Polish troops were in bivouac and resting, with some of their wagon trains and troops still on the road to battle area, whereby a possible enemy attack upon the disarrayed Polish royal encampment could have caused serious damage. The Crusader's however, while being fully deployed, had suspected a trap and did not dare to attack.

Grand Duke Vytaut urged King Jagello several times to expedite the movement of his troops to their proper positions as time was essential, but Jagello attended a field mass for his troops. The purpose of his actions at this time was never satisfactorily explained, but they certainly provoked the Teutonic Knights to anger, because the Knights waited fully three hours in hot sun, sweltering in heavy armor, waiting for the battle to commence, although they themselves refused to attack and disrupt their own plans.

In due time Vytaut signaled a cavalry detachment composed of Samogitians and Tatars, dressed as uniformed Lithuanians, to make their highly specialized frontal assault on the enemy. This cavalry detachment engaged the Crusaders in physical combat for a brief spell, the purposely veered off in hasty retreat to lure the overconfident Crusaders into a trap. With a taste for quick victory, the Crusaders, in hot pursuit of the enemy, were suddenly encircled by a flanking movement of Vytaut's cavalry, which veered to the right and attacked the Crusaders from the rear. The remaining Germans were too disorganized, in broken ranks, to regroup their forces in a unified effort to save the day. For them the battle was lost.

The battle plan outlined by Grand Duke Vytaut worked to perfection, and the Teutonic Knights succumbed in what is considered to be the last great battle of their history.

In Prince A. M. Kurbsky's letters on Ivan IV appears one of the written notes of a Crusader who participated in this battle, as he states : “Leaving other things aside, I will tell you of one fierce battle which we had with Grand Prince Vytaut of Lithuania, when in one day six Masters were appointed and one after another they were killed, and we fought fiercely until the darkness of the night dispersed the battle”.

From Polish sources, as elicited by novelist Henryk Sienliewicz, an expert student on this battle, in his famous novel, The Teutonic Knigths, we get a vivid picture of the hand-to-hand combat in this battle – and of the genuine respect for the fighting skills of the Samogitians : “The Samogitians were indeed splendid figures. In the light of the fires their broad chests and powerful arms could be seen under their sheepskins. Every one of them was dry, but bony and tall; in general they surpassed in physique the inhabitants of other Lithuanian districts...” Of the famous Samogitian warrior horses, he said: “Allies were amazed by the shaggy bodies of the Samogitian ponies, which were unusually small, with powerful shoulders, and in general were so strange that the western knights took them for some entirely different kind of forest beast, resembling unicorns more than real horses.... veterans of former service with Duke Vytaut explained to newcomers that large war stallions were of no use here, because a large horse would sink at once in the bogs, while the ponies were able to pass everywhere as easily as a man.... A German was unable to escape if he were fleeing from a Samogitian, nor was he able to catch a fleeing Samogitian, for these horses were as swifts as, or even swifter than, the Tatar breed”.

Relating about Samogitian fighter, Sienkiewicz continues: “Only they fight in a disorderly crowd, and the Germans in serried ranks. If one can break their ranks, then a Samogitian will more frequently slay a German than a German a Samogitian”. In describing the Samogitian's adaptability to hidden positions, he further states: “The Samogitians, accustomed as they were to forest life and warfare, dropped down skillfully behind tree trunks, mounds of earth, hazel bushes and tufts of young firs, as if the earth, hazel bushes and tufts of young firs, as if the earth had swallowed them. Not a man spoke, not a horse snorted. From time a small or large beast of the forest passed by, and only when it had nearly touched them dashed aside, panting with terror. At times a breeze rose and filled the forest with solemn and majestic sound; at times all was still, and only the distant calling of the cuckoos and the near-by hammering was to be heard. The Samogitians listened to these sounds with joy, for woodpeckers, especially, they regarded as heralds of good tidings”. On a particular incident on their scouting missions, Sienkiewicz relates: (It rained the night before the battle, so they used this contrivance to prevent detection. They scouted continuously throughout the battle, relaying their reports to headquarters until cessation of hostilities) “... a Samogitian on a shaggy pony, whose hooves were wrapped in sheepskin, so as to make no clattering and leave no tracks in the mud”.

In regard to their armament, he wrote: “They were all well armed; they had not, it is true, the powerful 'trees' or lances which the knights were wont to use, but which would have been a great hindrance on forest marches; but they held in their hands short, light Samogitian pikes for the first attack, and had swords and axes at their saddle-bows for fighting in a press”.

Then Sienkiewicz describes their valiant and intense confrontation with the enemy in the heat of battle: “From both sides of forest rose the terrible cry of Samogitian warriors. Hosts of them rushed out of the thickets like an angry swarm of wasps whose nest a careless traveler had disturbed with his foot. But they charged without success. The Germans stuck the butt ends of their heavy spears and halberds into the ground and held them so evenly and firmly that the light Samogitian ponies could not break the wall...the Samogitians hewed with their sword-blades at the spear-points and shafts, from behind which looked out the faces of men-at-arms, paralyzed with amazement and drawn by stubborn determination. But the line did not break. The Samogitians also, who had attacked from the flanks, sprang back again from the Germans as from a hedgehog. They returned soon, it is true, with greater impetuosity, but could accomplish nothing.... Some climbed in the twinkling of an eye into the trees by the road-side, and began to shoot into the midst of the men-at-arms, whose leader, seeing this, gave command crossbowmen began to shoot back, and so from time to time a Samogitian, concealed in the branches of a pine, fell to earth like a ripe cone, and dying, tore the moss of the forest with his hand or writhed like a fish out of water. Surrounded as they were on all sides, The Germans could not, it is true, count on victory; but seeing the success of their defense, they thought at least a handful might succeed in escaping from the straits they were in and getting back to the river.... no one thought of yielding, for, as they themselves gave no quarter, they knew that they could count on no pity from a people brought to revolt and despair. Hence they retreated in silence shoulder to shoulder, rising and lowering their spears and halberds, cutting, shooting with their cross-bows, as far as the confusion of battle permitted, and drawing nearer all the time to their horsemen, who themselves were engaged in life-and-death struggle with other detachments of the enemy.... From the flanks the Samogitians attacked again. The whole detachment, which up to that time had stood firm, was rolled up, shook like a house whose walls are burst, split like a log under a wedge, and finally broke... The battle instantly changed into a slaughter. The long pikes and halberds of the Germans were useless in such a press. On the other hand, the horsemen’s sword blades bit into skulls and necks. The horses reared up in the crowd of men, overthrowing and trampling the miserable men-at-arms. It was easy for the horsemen to strike from above, and they did without taking breath or rest. From the sides of the road rushed forth ever-new hosts of wild warriors in wolf skins, with a wolfish lust of blood in their hearts. Their howls smothered the voice of those begging for mercy and drowned the groans of the dying. The vanquished threw away their weapons; some tried to slip into the forest; others fell on the ground shamming death; others prayed; one, apparently beside himself with terror, began to play on a whistle, and then smiled, looking upwards, until a Samogitian sword split his skull. The forest ceased to sough in the wind, as though terrified at death... At the least a handful of Teutonic warriors melted away. A wave of Samogitians on horse and foot surrounded them closely, but they defended themselves, cutting and thrusting with their long swords so fiercely that a semi-circle of bodies lay before the horses' hooves. Then the knights perceived that the battle was lost, and naught was left save break through the detachment with cut off the retreat, or perish, but the German horses were not good for flight and the swifter Samogitian ponies overtook them, inflicting the final blows. Scattered Germans fled like a herd of deer, with intolerable fear in their hearts. Some got away into the forest; but one, stuck in the mud as he was trying to cross a stream, was strangled by the Samogitians. The remainders were followed by whole bands into the thickets, which soon became the scene of wild hunts, ringing with cries, shouts and calls. The depths of the forest long resounded with them until the last German was finally caught. Too many, both of the Samogitians and of the Germans, had fallen for it to be possible to bury them”. So wrote a Polish novelist who availed himself to study the situation to the most intimate details, bearing testimony to the unimaginable savagery, and the terrible ferocity of the battle between the Samogitians and the Teutonic Knights. One can only ask himself: “What price glory? What price religion? What price humanity?”.

According to the chronicles: “the fleeing enemy (Teutonic Knights) was chased until sundown, at 8 o’clock in the evening, when the battle was considered as being ended”.

Even before the battle ended, most of Polish troops and their mercenaries indulged in looting the enemy camp, which was full of great riches; but the battle-disciplined Lithuanians and Samogitians immediately forsook any such efforts to care for the casualties among their brothers in arms who fought beside them so faithfully, and secondly, to care for the captives – they were still concerned with matters of life and death.

King Jagello had no objection to the division of spoils by troops, but he ordered that wine casks be smashed and the wine spilled on the ground lest the soldiery get drunk and disable themselves in the event of an enemy attack. It is therefore assumed that King Jagello was not at this time aware that the Teutonic Knights were practically annihilated.

With the exception of the Hospitaler Wernher von Tettingen, who succeeded in flight, all of the Order's top command met death on the battlefield – from Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen and Grand Master Friedrich von Wallenrode, on down. Marquard von Saltzbach, the Komtur of Brandenburg, and former friend of Grand Duke Vytaut, was ordered to be executed for his insulting behavior in captivity after the battle, but Samogitian sources intimate that Vytaut never forgave him for his dereliction of duty in the battle of Vorskla in 1399. Vytaut blamed von Saltzbach for losing the battle because he failed to curtail the drunkenness of the Crusaders, and because he failed to prepare his troops in time to take up their proper battle positions. Heinrich Schaumburg, the Voigt of Sambia (Samland), and Jurge Marschalk, the “kompan” of the Grand Master, also were executed for similar reasons.

The following day, Wednesday, July 16, 1410, bodies of the fallen Grand Master and other dignitaries of the Order were located and identified on the battlefield. The corpses were dressed in purple, shrouded in clean white sheets and taken to the Crusader headquarters at Marienburg (Marlbok) for burial. The others, friend and foe alike, were solemnly buried with three requiem masses held and the entire army in attendance. This was a most impressive ceremony for formal reverence for the dead. In the mystery of life, this highest display of dignity often manifests itself among the survivors of the most viciously fought encounters in mortal combat. The survivor's only solace being, “This could have been me”.

Immediately after the burial services, messages were delivered to inform the Samogitians of an impending attack on their homelands by the same Tatar army that devastated Moscow a year before. Not realizing they were victims of another ill-conceived plot by Vytaut and Jagello, the Samogitians hastily departed to defend their homeland. The messages were utterly false and undoubtedly concocted by the clever “ruler cousins” so that they could negotiate with the Order for their own benefits, with the intentions of using the Samogitians diplomatically as pawns. The irony of this fraudulent incident is that no Lithuanian or Pole offered to aid Samogitian in defending her homeland in this vital hour. And for those historians who delight in using Vytaut's name as king of Samogitia, it is most difficult to explain why he, an aggressive leader, should not be the first to defend Samogitia and to rally his Lithuanian troops for the same purpose in this desperate time of need. But instead, the great “cousin rulers” were preoccupied in personal satisfaction. They held a state banquet attended by Polish and Lithuanian dignitaries, with some prisoners of war as guests, as Prince Konrad of Olesnica and Prince Casimir of Stettin, in addition to other prominent knights.

The Lithuanian and Polish troops then attacked Marienburg Castle without success, and finally resorted to siege tactics. After six weeks of the siege, Grand Duke Vytaut had no further taste for this type of warfare and departed with his troops for Lithuania. Meanwhile, King Jagello held the Teutons under siege for two more weeks, but according to Polish Canon Dlugosz, the Poles were “inexperienced and negligent”. Disease and dysentery struck their camp because of undisciplined field sanitation practices. In large measure, this was due to the fact that they lacked campaign or battle experience, which would have made them proven troops.

The Polish nobles were disgruntled and wanted to return home for the harvest season, and they also worried about rumors of Hungarian incursions into their homelands. The mercenaries were demanding their pay in arrears and Jagello had no funds available. To add to his woes, there was a shortage of munitions. He was forced to yield to his nobles and departed in the footsteps of his cousin, Vytaut, on September 19, 1410.

For the sake of history, it is indeed a tragedy to learn of perfidies committed, in false pride, by prejudiced who distorted important events to the benefit of their respective countries; but, in the studies of the battle of Tannenberg, the facts contradict such distortions, Alfred Rambaud in his Russia volume one, stated: “... the Lithuanian army consisted of 97,000 Infantry and 66,000 Cavalry, while the Knights and 57,000 Infantry and 26,000 Cavalry”. Historians James Thompson and Edgar Johnson wrote in their book An Introduction to Medieval Europe 300-1500: “In 1410 a motley Polish-Lithuanian army of some one hundred thousand men that included Czech mercenaries, Tatar chieftains, Russian boyars, and skin-clad Samogitans invaded Prussia and met the army of the Order (35,000) not far from the village of Tannenberg, where they defeated it so thoroughly that the military power of the Knights was broken for good”. The German and Samogitian figures for this battle more or less approximate each other. The Lithuanian figures are out of line with most of the others, and the Polish are utterly fantastice in every aspect

At first, the Poles magnify the importance and immensity of this battle. Then they derive such minute numerical ratios for all other battle participants that it makes themselves appear as gigantic in all aspects of this victory. The forces of King Jagello consisted of 7,000 Poles and 7,000 Czech and others mercenaries; yet the losses sustained in their sideline skirmish were about 1,000 killed, at most, with about an equal number wounded. Meanwhile, the Lithuanians lost about 6,000 men, with between 10,000 and 15,000 listed as being wounded. The Samogitians lost 3,000 in action, with slightly more than this in the wounded ranks, out of their full complement of 12,000 men. The Tatars suffered 100 deaths with about 200 wounded from their detachment of 400 troops. They were commanded by Khan Soldan, a staunch friend of Grand Duke Vytaut. The allied totals of men killed were about 10,000, and the wounded toll was between 20,000 and 25,000 victims.

The Teutonic Knights lost about 18,000 men killed in action, as they claimed, with about 30,000 wounded and several thousand listed as captured. About 2,000 of their troops succeeded in retreating to their stronghold at Marienburg under the leadership of Heinrich von Plauen. They successfully withstood the siege of Grand Duke Vytaut's and King Jagello's forces, which lasted for two months.

In commentaries relating to the battle to Tannenberg, Samogitian sources are greatly disturbed by the misconceptions of their classic maneuvers in it. Some historians persist in stating that the classic maneuver in this battle was copied from the Mongols, and it is called the “Tulughma”, which is the swift envelopment of the flank in a swift “standard sweep”. The Samogitians defensively quote the Soviet historian V. T. Pashuto, who notes that the adroit Samogitians used these tactics as early as 1132, about 100 years before the Mongols came to Europe. He quotes Knyaz Daniel Romanovich in referring to their expertness: “... just as space in the Citadel for Christians, so the narrows are for the heathens (Samogitains)”.

Ironically, some prejudiced historians will find that a simple sentence published in The Cambridge history of Poland (to 1696) will always remain a thorn in their sides as long as it remains in print, stating: “Even in Swiss and French chronicles Tannenberg is presented as a victory of the 'Saracens' (Samogitians)”.

The Lithuanian historian Constantine R. Jurgela minimizes the influence of Russians in part of the battle of Tannenberg by noting that the Muscovites had not even heard of the battle until the 19th century. In his book Tannenberg, he stated: “Indeed, had Vytaut and Jagello succumbed in 1410, the Teutonic tide might have rolled on to the plains of Russia and provided a reason to speak of a 'Teuton-versus-Slav' struggle. From the point of view of historic truth, that slogan is just an invention of propagandists.

“The Muscovites and the Great Russian people for several centuries had known nothing of this battle, until the birth of Pan-Slavism. On the other hand, Lithuanians (C. R. Jurgela fails to distinguish between Samogitia and Lithuania. He groups both elements under Lithuania proper) and Poles not only had fought in that bloody conflict but retained vivid memories thereof in their folklore as lately as the 16th and 17th centuries (see Albert Wiiuk-Koialowicz, S. J., Historiae Litvaniae, Danzig 1650, and Bellum Prutenum of 1516 of Joannes de Wislica). Their statesmen enjoyed the fruits of this victory. No such lingering memories are to be found among the monuments of the Byelorussian and Ukrainian peoples, not to mention the Great Russians. The Russians had played no part in Lithuania's internal affairs until the period of occupation by troops of Tsar Peter I in the 18th century. The Ruthenes, Byelorussians and Ukrainians began to play an active and important role in the state of Lithuania only toward the end of the 15th century, when they acquired a sense of citizenship in common”.

Because Poland permitted heathen reinforcements to do battle against the Crusaders at Tannenberg in violation of the terms in their peace pacts with the Teutonic Knights, the undaunted and much-angered Grand Master Heinrich von Plauen wanted to take punitive action against it.

Two months later he had recruited enough knights to build up an army of 11,000 men, while King Jagello could raise no more than 7,000 men, and failed to get support from Lithuania or elsewhere.

If the victory of Tannenberg had been made the most of, the Order of the Knights of the Cross would have been completely destroyed. But the Poles, occupying the Prussian cities, immediately united with Poland in a move Grand Duke Vytaut called “greed”. The disturbed Vytaut opposed these ventures of aggrandizement by Jagello and decided to become a force of subtle opposition to Poland.

Vytaut himself saved the Order from utter ruin by not assisting the Poles to wage war, and while taking part in the Treaty of Thorn, he arranged the easiest terms possible for the Order. He had to contend with the Poles in the future, who continuously exhibited pretensions toward the state of Lithuania. He did not wish the Poles in the future, who continuously in strength, and desired to plague them with oppositions, covert or otherwise.

The insecure Jagello persuaded Grand Master von Plauen to talk of peace, in hopes that “the ancient amity” would again prevail between their countries. They finally resolved their differences and together, with Grand Duke Vytaut, signed the Treaty of Thorn on February 11, 1411.

The Treaty of Thorn provided for restoration of pre-war frontiers, with the exception of Samogitia, which was on of the spoils theoretically to remain with Lithuania until the death of both Vytaut and Jagello – and then was to revert to the Order. The ransom of Teutonic prisoners was set at 300,000 Hungarian ducats. The Knights were to pay 100,000 kapas of groszen in reparations to the allies for war costs. The issue of Drezdenko and Santok was to be arbitrated by the Pope. Jagello was to give up his usurped title of Prince of Pomerania. Promises of future actions against each other were not permissible. And Vytaut and Jagello were to strive to convert the heathen infidels of Samogitia.

The befuddled Samogitians were completely ignored in all peace discussions. The Polish-Lithuanian gratitude for Samogitia's tremendous efforts in the victory of Tannenberg, in which she suffered many casualties, was exemplified in the unprincipled diplomatic agreements concerning her by the deceitful cousins, Grand Duke Vytaut and King Jagello. Perhaps the intentions of the latter two was to convince the Teutonic Knights and western Europe that no peace pacts were violated by either of them, because no Samogitian heathens had participated in the battle of Tannenberg.

The irate Samogitians, in rebuttal to the implications of the Treaty of Thorn, again circulated literature throughout Europe, denouncing Lithuanians and Poles, and stating that none but true Samogitians could sign any treaty involving them, and that the Treaty of Thorn should be recognized as a contemptible affront to the Samogitians.

The following year or two was too peaceful for both Vytaut and Jagello. Apparently they could not live without each other, as well as with each other, at least on the surface. This was called the “era of good feeling” between them, and it afforded an opportunity to cement relations between Lithuania and Poland in a new alliance signed December 2, 1413, called the Pact of Horodlo. A significant aspect to this signing was the creation of 47 titles of nobility by the Poles, awarded to 47 Lithuanians selected by Vytaut, in a gesture to weaken Lithuanian opposition to the pact. (Among the 47 lithuanian nobles, Jonas Gostautas who fought in Tannenberg under Vytaut, received the “Habdankas” Coats of Arms in behalf of his family).

To outwardly show good intentions of fulfilling their obligations in the Treaty of Thorn, both Vytaut and Jagello, together, made some pretensions to baptize the Samogitians by touring outlying districts and supposedly baptizing people in large groups. The entire procedure was mystic and unchristian in spirit so as not to antagonize the Samogitian general populace.

For reasons as yet unexplained, the first indication of outside concern for the welfare of the heathen Samogitians, and perhaps in response to one of their appeals to all Europe, came from a man of God. This man was Gregory Tsamblak (Camblak), a Bulgarian, appointed as Metropolitan of Kiev and Orthodox Lithuania, who had great respect and compassion for the Samogitian people, and asserted his influence in their behalf at Grand Duke Vytaut's court. He urged King Vytaut (his title by Russian sources) to side with Eastern Europe in the name of peace. He pleaded with Vytaut to become an Orthodox and to discontinue his affiliation with “the Polish faith”. Vytaut replied: “ If you wish to convert not only me, but also the infidel inhabitants of my country... go to Rome and debate with the Pope and his councillors. If you should fail, I shall convert all the Christians of your faith resident in my country into my German (Vytaut was baptized by Germans as WIGAND) faith”.

Metropolitan Gregory Tsamblak accepted Vytaut's challenge and immediately negotiated with the Samogitian Princes and Elders to accept his propositions in the name of peace for all time. Impressed by his reverance and favorable composure as a man of God, the Samogitians accepted his persuasive appeals.

The Metropolitan then made overtures to the Pope in Rome which would, in effect, join his Orthodox Church with the Roman Catholic Church. This was contingent upon solving the Samogitian issue to their satisfaction. Specifically, the Samogitians claimed they were a separate and sovereign nation, perpetuating a very ancient kingdom; and insisted that an emperor cannot grant titles to the lands of the heathens, inasmuch as he is not and independent sovereign, but is dependent on the Pope.

Arrangements were also made by the Metropolitan to have the Samogitian crown prince and 60 other Samogitian princes attend the 16th General Church Council in Constance, Germany – to plead their case against the injustices of the Teutonic Order. The Metropolitan wanted them to convince European public opinion of the illegitimacy of the Teutonic Order's claims, and to undermine the reason for the very existence of this Order.

It is said that Grand Duke Vytaut, himself, baptized en masse the 60 Samogitian Princes into Christianity before the departed for Germany, so that they could make their appearance at the General Council as Christians, but there is little credence to this assertions.

Just as winter was setting in, in November of 1415, 60 Samogitian princes and four Elders, led by their young Crown Prince Kynrint, arrived in Constance, Germany, for the 16th General Council of the Holy Roman Empire. They were accompanied by Gregory Tsamblak, the Metropolitan of Kiev, and organizer of the journey who endeavored to placate the Catholic Church, so that the Samogitians would be adjudicated without prejudice in their favor. The Metropolitan invited the Khan Soldan, son of the late Khan Tokhtomysh, to accompany them on this journey. His motive in having Khan Soldan plead in behalf of Samogitia at this General council was to show that his ancestors, the Mongols, had fought the Samogitians for almost 200 years, and now that their differences were resolved amicably, they were living in peace – therefore there was no reason on earth that the Teutonic knights could not make peace in the same manner. Gregory Tsamblak also wanted to show western Europeans what a true Saracen was in the appearance of the Khan Soldan, to dispel the myth propagated by Teutonic Knights that the Samogitians were Saracens.

On their journey, they attracted many thousands of Europeans, who often traveled great distances just for a glimpse of the dreaded and legendary Samogitian warriors who defied the Crusaders by making this tour, and who had, a few years back, vanquished the noble Teutons at Tannenberg. The handsomeness and gentility of Samogitian princes unexpectedly startled the crowds, who had anticipated seeing them as Saracens or Mongols. The exceptionally fine actors and performers accompanying the princes put on such fantastic shows that overwhelmed populace took the samogitians to their hearts in every town on their way to Constance. This was also a psychological strategy devised by the Metropolitan Gregory Tsamblak to win over the people, and it worked perfectly to the benefit of the Samogitians.

An outstanding impression, which the noble houses of western Europe talked about many years later, was the exceptional quality of the Samogitian furs worn by princes, and of their splendid horses which were beyond compare.

At the General Council hearing the Samogitia affairs were handled by their four Elders and two Lithuanian advisers, using a Polish priest as their interpreter and translator. Their complaint, written so artfully and with so much erudition in espousing their cause, made a profound impression at Constance. The Order, much displeased at the show of sympathy for the Samogitians, could not with good grace object to the Samogitian appeal.

From Richental's chronicle, as translated by Louise Ropes Loomis, in her book The Council of Constance, we learn that the Council decided in favor of Samogitia, upholding her sovereignty as a valid kingdom and recommending that Samogitia be part of the Holy Roman Empire. This historic decision invalidated all previous fraudulent claims to Samogitian territory by pretenders such as Grand Duke Vytaut, King Jagello and the Teutonic Knights. An extract from Richenthal's chronicle states: “The Teutonic lords from Prussia answered that they had once conquered that people (Samogitia) with the sword and that they belonged to the Archbishopric of Riga in Livonia, which was the Prussians' province. If the people desired to become Christian, the lords and Archbishop would make them Christian. But the assembled Council forbade the Teutonic lords to do this and commanded them by their obedience to the Council to put no more obstacles in the way of that peoples and to have no more to do with them. Henceforth the Samogitia should be part of the Holy Roman Empire and in spiritual matters to its bishops and priests”.

Throughout the winter of 1415-1416 the much admired Samogitian princes were entertained by may noble houses of Europe, who vied with each other for honors to do so. The nobility of western Europe was eager to gain more knowledge of the Samogitian people and their history, especially of their many battles with the Mongols of the Golden Horde. That winter became one of great social activity for the Constance. The residence of the crown prince of Samogitia in the city of Constance was quickly labeled as the “House of the Sun” (History records that when Metropolitan Gregory Tsamblak returned to the General Council in 1418, threatening to establish a third Rome in retaliation for the Council's failure to carry out its decision supporting Samogitia, he resided while in Constance at the “House of the Sun”.) by the townspeople. This was due to the Prince's attachment of his family shield with its sun emblem on the entrance of the building in recognition of the establishing it as his official headquarters during his stay in Constance.

The wealthy Medici family of Florence, Italy, was so impressed with the Samogitian princes' visit to the city of Constance that they commissioned the artist Benozzo Gozzoli to paint a scene on the walls of their family chapel in memory of the famous event depicting the journey from Samogitia to Constance. As time went on, the significance of the painting was lost in antiquity. A myth concerning it was developed, due to ignorance of historical fact by later art connoisseurs, who (lacking a proper interpretation) concluded that it portrayed a Christmas scene; and as a consequence erroneously labeled it “The journey of the Magi” . But today, through the revelation of the present hereditary Grand Duke of Samogitia, Bernard B. Blazes, who described in detail all aspects of the journey, as incorporated into the painting, from notations still perpetuated in his family history, it is now concluded that the error stands to be corrected, for posterity to note and historians to record. He explains: “This painting symbolizes an episode of a great event in my family history. It depicts my ancestors and a host of their relatives journeying to Constance, Germany, to attend the 16th General Council in 1415, in defiance of the Teutonic Crusaders, for a confrontation with all Christendom.

“The so-called king, on the left side of the painting, is none other than the Crown Prince Kynrint, who, at the time, was about 16 years old and too young to be king by Samogitian law. To the right, are his twin brothers, John and George, who were several years older than the crown prince. As young children they were captured by the Teutonic Knights and held captive for about five years. They were baptized as Christians by the Knights and retained their Christian names the rest of their lives. Shortly before the Battle of Tannenberg a Scottish Knight of the Teutonic Order defected to Samogitia with the twins, returning them to the safety of their homeland. In this painting, it is evident that only members of the Royal Family wore ermine. One brother was Keeper of the Royal Sword and the other was Keeper of the Royal Seal. The so-called king, in the center of the painting, is actually the Khan Soldan, son of the famous Tatar, Khan Tokhtamysh. Khan Soldan and his troops volunteered their services in the Battle of Tannenberg to fight alongside the Samogitians. To the far right, the so-called king is the reverential Bulgarian, Gregory Tsamblak, the Orthodox Metropolitan of Kiev, who organized the journey and was responsible for its success. He was very much admired as a religious man by my ancestors. To the far left is the Polish priest Nicolas Sapienski who was assigned by Grand Duke Vytaut of Lithuania to accompany the Samogitian princes as their official interpreter and translator at the Council. Alongside the Polish priest are two Lithuanians, Georges Gedigaudas and Georges Galiminas, also appointed by Grand Duke Vytaut as official advisers. In the other details of this painting, a few bearded Samogitians are noted, and the extended group of horsemen are the 60 warrior Samogitian princes, most of them relatives of the crown prince. Others in the painting, besides the onlookers, are the actors and entertainers who performed for the people in the various towns on their route to Germany. The emblem in the top of the painting, is an embellished design of my family symbol, dating back to the most ancient times, and from which it derived its name, “The House of the Sun”.

Samogitian Princes travelling to attend Constance’s Concile in 1415.

On their return to Samogitia from this mission, in March of 1416, the princes ordered the delivery of a herd of bison to Constance, Germany, as gifts to various nobles in gratitude for the hospitality and social treatment bestowed upon them during their winter stay in the city of Constance. As the bison was an unfamiliar animal to the west Europeans, the nobility expressed a desire to see them. They were tantalized with a further desire to eat bison steaks, after learning of their succulent quality from the Samogitian princes.

By the latter part of 1417, the forced Christianity upon Samogitian became short-lived because the adjudication of the General Council at Constance was not enforced. Uprisings occurred among the deceived Samogitian pagans, who refused to relinquish their ancient forms of worship, and directed their vengeance on the new nobles of Grand Duke Vytaut's choosing. The Royal Family of Samogitia was the first to revert to paganism and swore vengeance on Vytaut. They had learned from friends in Constance that the Grand Duke Vytaut never expected the Council to render a decision in favor of Samogitia, and he was therefore more disappointed with the outcome than Teutonic Crusaders. It was Vytaut who wasted no time in instigating important officials at Constance not to enforce their adjudication in Samogitia's behalf, because he had just as much to lose as the Crusaders by its enforcement.

Subsequently, the Teutonic Order continued hostilities with Vytaut and Jagello over the supposed jurisdiction of Samogitia. The litigants finally decided to permit Emperor Sigismund of the Holy Roman Empire to act as arbiter. At an imperial Congress of members of the Holy Roman Empire, held at Breslau in 1420, without any Samogitians being invited, the Emperor rendered a verdict in favor of the Teutonic Order, adjudicating Samogitia to them.

Vytaut and Jagello attempted to annul the verdict by direct negotiations and by direct appeals to the Roman Curia – but the Order had the Emperor and German princes behind it and would not renounce its claims. The issue was again decided by arms, exclusively by Samogitians on their own. In 1422, the irate Samogitians, in full force, attacked all of the Order's possessions in their territory and succeeded in destroying them and almost destroying the Order, too.

The clever opportunist Vytaut then threatened the Emperor by proposing to accept the crown of Bohemia, which the Emperor himself coveted. These acts forced the Grand Master of the Order to sue for peace when no further help from Western Europe was available. The peace was negotiated at an army camp on the shores of Lake Meln in Prussia on September27, 1422. This pact ended the long territorial dispute, and thus the Order renounced forever its former claims to Samogia.

Although some historians allude to the Teutonic Order's desires to Christianize the heathen Samogitians, while other historians express the fact that the Order was motived purely by territorial aggrandizement, and because the Samogitians prevented them from acquiring a direct land bridge to the lands of the Livonian Order, in Latvia... the Order pursued an unrelenting policy to conquer or eradicate these people. But another little-known reason, and perhaps the most justifiable one, for the Order's persistent desires to conquer Samogitia, as well as Grand Duke Vytaut's covetousness for it, is revealed by the present hereditary Grand Duke of Samogitia in explaining the mystery thusly: “The Crusaders were land pirates at heart. They, and Grand Duke Vytaut, were aware of and tantalized by the great hidden treasures in Samogitia... The war booty captured from the Mongols of the 'Golden Horde'. The Crusaders kidnapped and tortured many important personages of the Samogitian nobility for a period of 200 years, vainly seeking the whereabouts of these treasures. This purpose, in my estimation, was the prime mover in all of their efforts to win the objective of Samogitia. But the Crusaders, as well as Vytaut, failed to recognize one mysterious aspect concerning this situation, which to this day remains a hidden force to reckon with. It dates back to the murder of King Ryngold in 1243 by the greedy Prince Mindaug, who later became king of Lithuania, because he was refused a share of booty for not having participated in the battles against the Mongols of Genghis Khan. The high priest of Samogitia then prophesied that these treasures would remain intact and untouched for a thousand years to come”.

Despite all the machinations of the forces trying to secure these coveted treasures throughout the past seven centuries, it still appears that the prophecy of the high priest of Samogitia will come true. Time will be the judge as we approach the year if 2243 A. D.

Lithuania Coats of Arms in 1415

Teutonic Order Castle in Malbork (Marienburg) - Pologne

Pierre Gochtovtt-Anglet le 26.01.2009